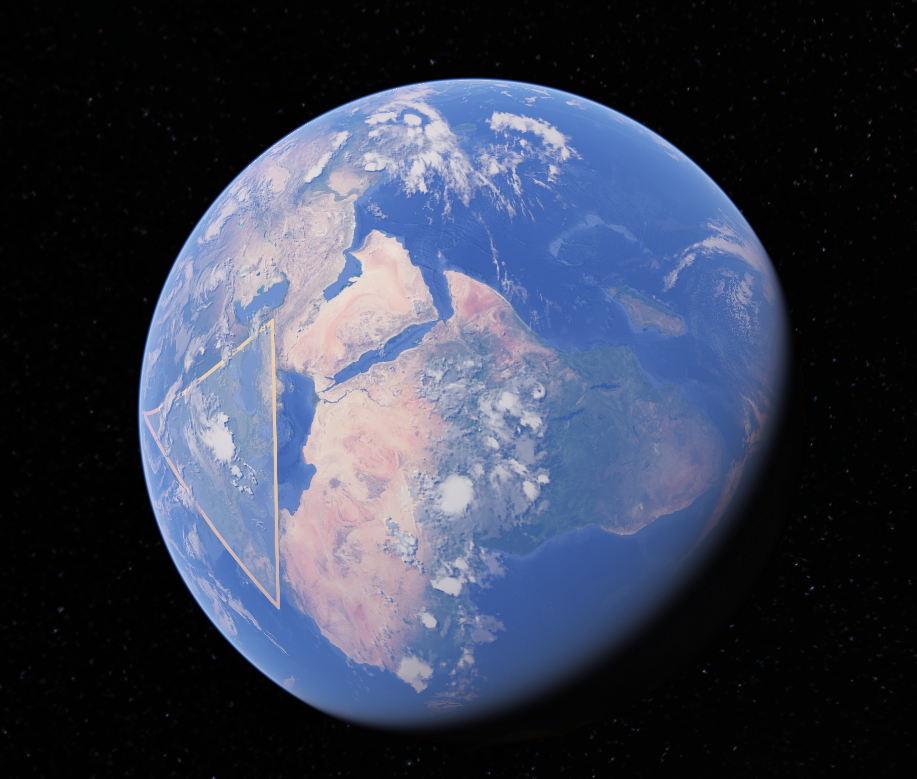

Europe is a somewhat contorted triangle at the Western extreme of Eurasia.

Like most other regions, Europe is habitually presented with north pointing up. Which is fine, that is a standard and standards help us take in geographical data without having to reorient ourselves. This the familiar, to us Europeans at least, standard representation™ of Europe (I’ve used Google Earth for all these projections).

However, going back to Europe being a triangle, more or less, to get different European perspectives we should go to the three sides of that triangle. Beginning with

Atlantic Europe

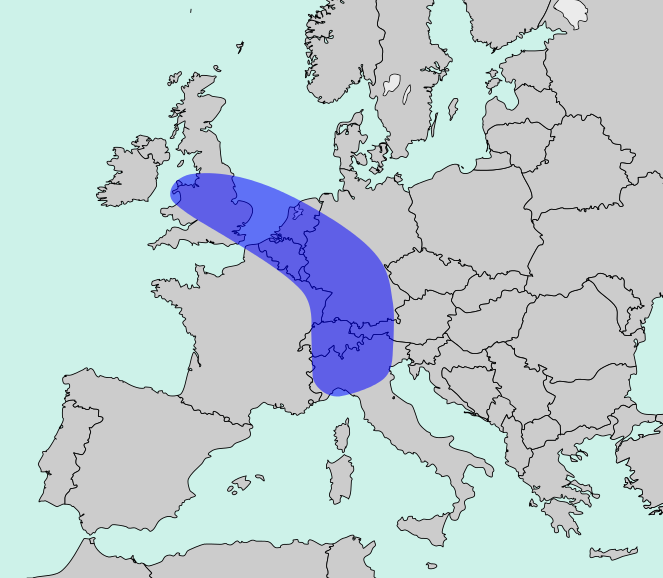

This is the dominant side, more people live to the west and they are overall richer. Viz the Blue Banana.

Also the Atlantic side is to a large extent Trans-Atlantic. What happens on the American continent, particularly North America, matters most.

(more…)